Foreverisms: Allan Gardner

Allan Gardner’s Foreverisms

By Barry Schwabsky

It happened while I was thinking about what to say about Allan Gardner’s art that I happened to see, on Instagram, a clip of Yohji Yamamoto, in which he says, “If you really want to see real things, real beauty, you have to go there by walking. And go there and touch it and smell it. Don’t use computer, otherwise you cannot get real emotion. If you want to create something you need real excitement, emotion—not superficial vision.” Of course, as much as I sympathize with what the great designer was saying, I had to reflect on the ironic fact that his wisdom was coming to me, not on account of my having walked somewhere to meet him, not because I had seen him face to face, shaken his hand, spoken to him, not through a direct connection—but through a form of vision even more superficial than that of the computer, namely of my iPhone.

And yet I insist there was some reality to the emotion I felt on hearing him speak from the heart. Superficial vision can go deeper than it seems. And that, in case, you’re wondering, is where Gardner comes in. I got to know his work through his 2022 New York exhibition “Distant Stars,” the subject of which was—as Maggie Dunlop wrote in the exhibition text, “how we reify our identities through the images we produce and the images we consume that prove we existed.” Though it was not immediately apparent what that show’s paintings and watercolors depicted, thanks to a painterly style that accented the materiality of mark-making over imagistic legibility, most of the works were derived from images found on a Tumblr page devoted to “girls and meth.” Creepy, right? But the work neither sensationalized nor romanticized the subject. It offered neither complicity nor judgement, but a close engagement with a rather disturbing reality—not so only the drug use itself but also its availability as a subject for voyeurism. To my mind, this had something to do with realism, and with the ethical demand that realism insists on, that one must not look away. But was I really looking at women smoking meth? The paintings themselves insisted that I was there, not with the meth smokers but with very rough depictions of them. Let me believe that Gardner had never gone in person to witness such scenes. Still, his depictions did seem to have a touch, a smell of the real. And the paintings embodied a kind of ugly beauty I felt I could in turn touch and smell and that perturbed me.

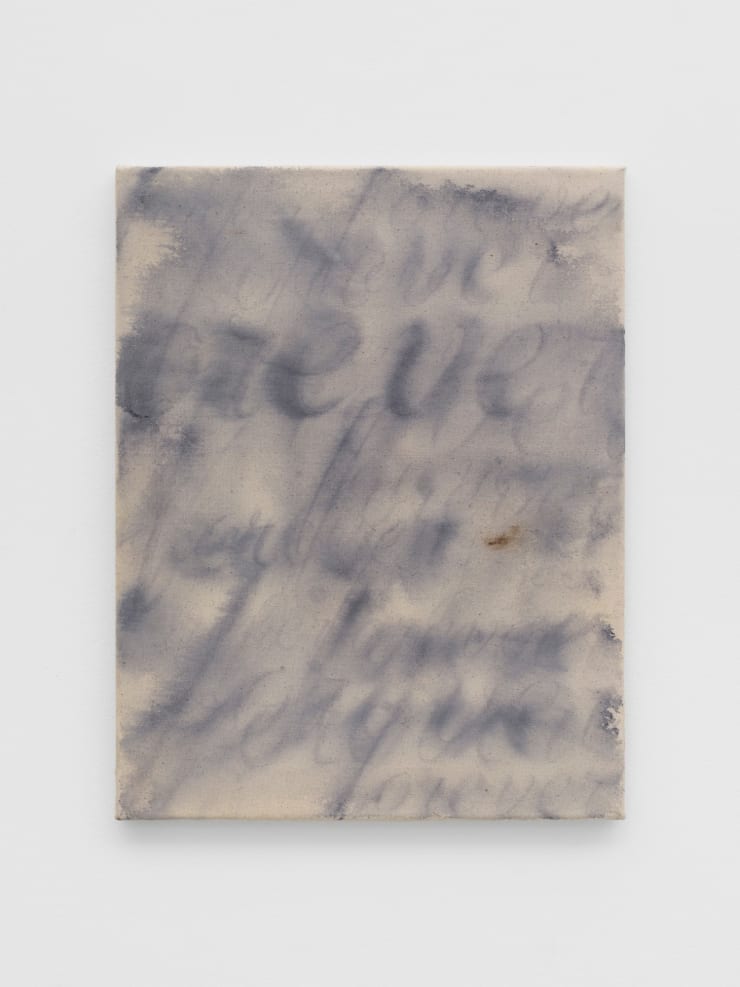

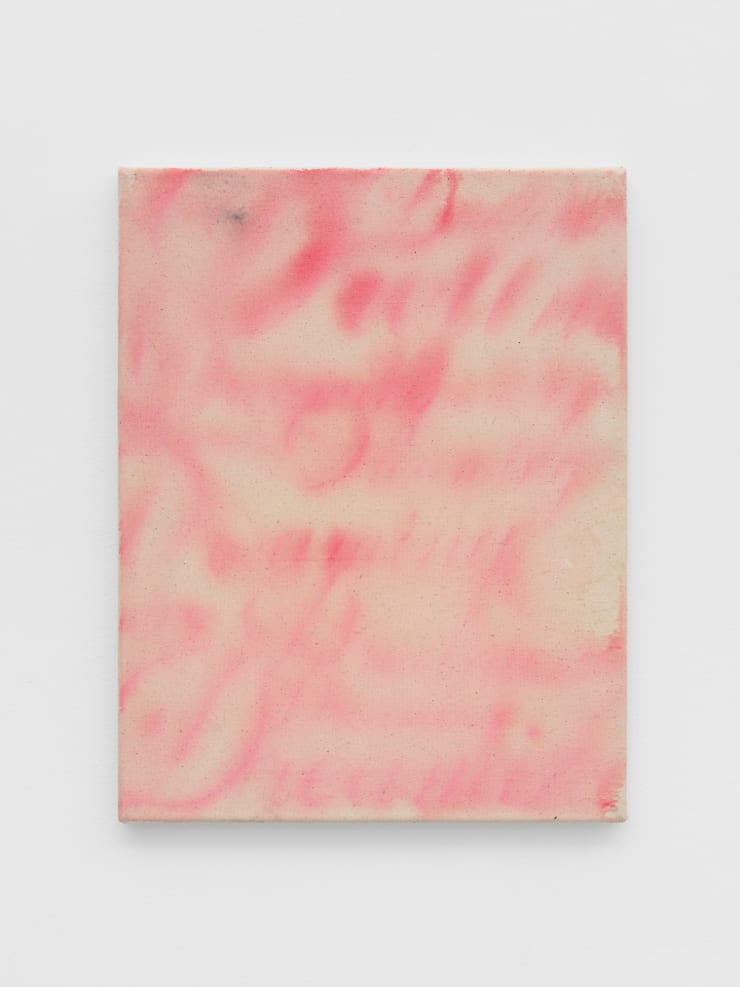

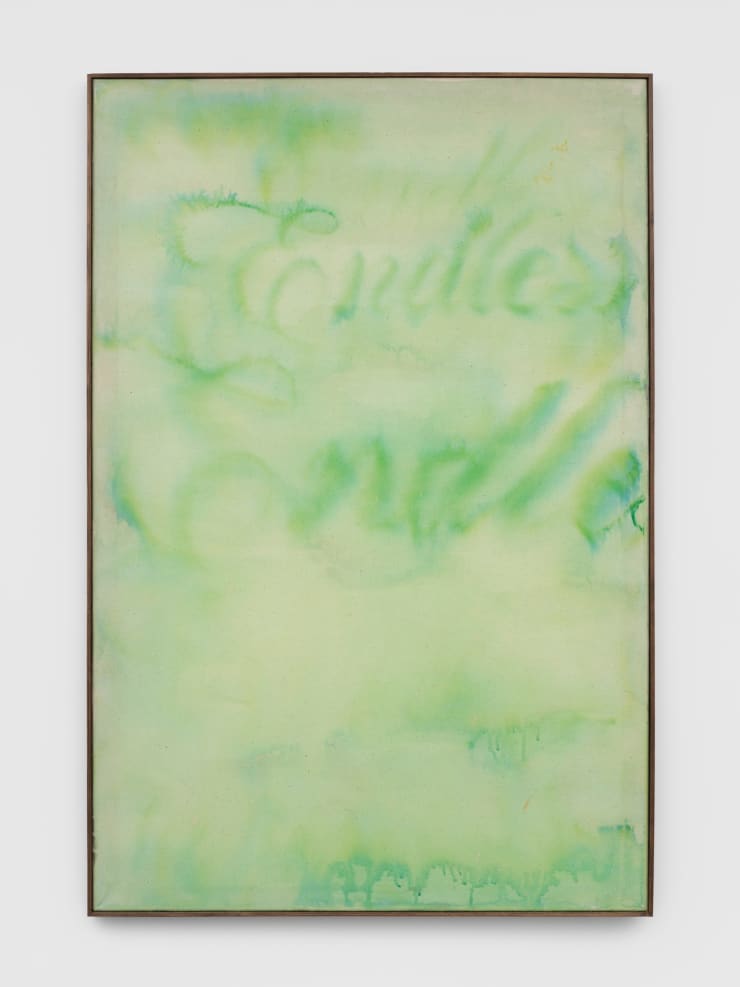

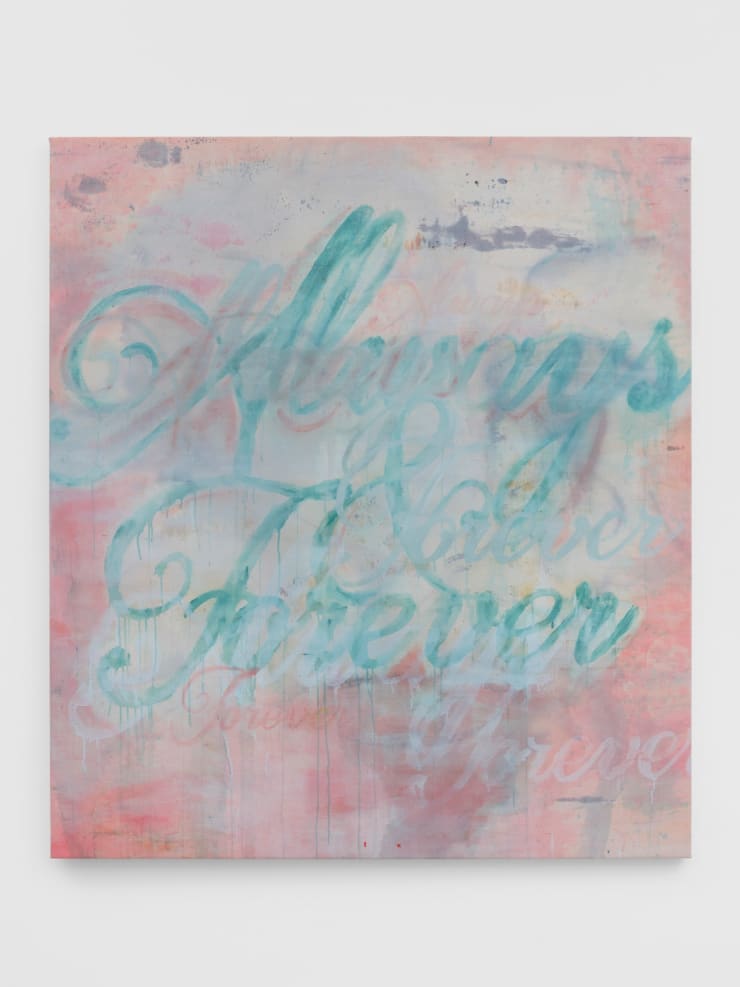

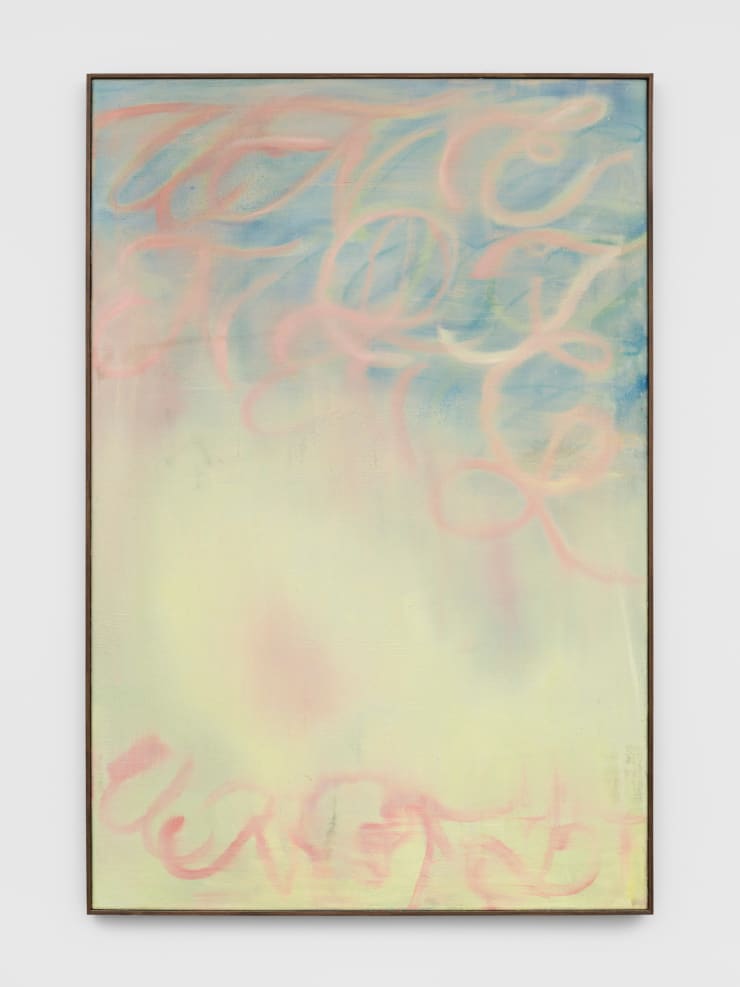

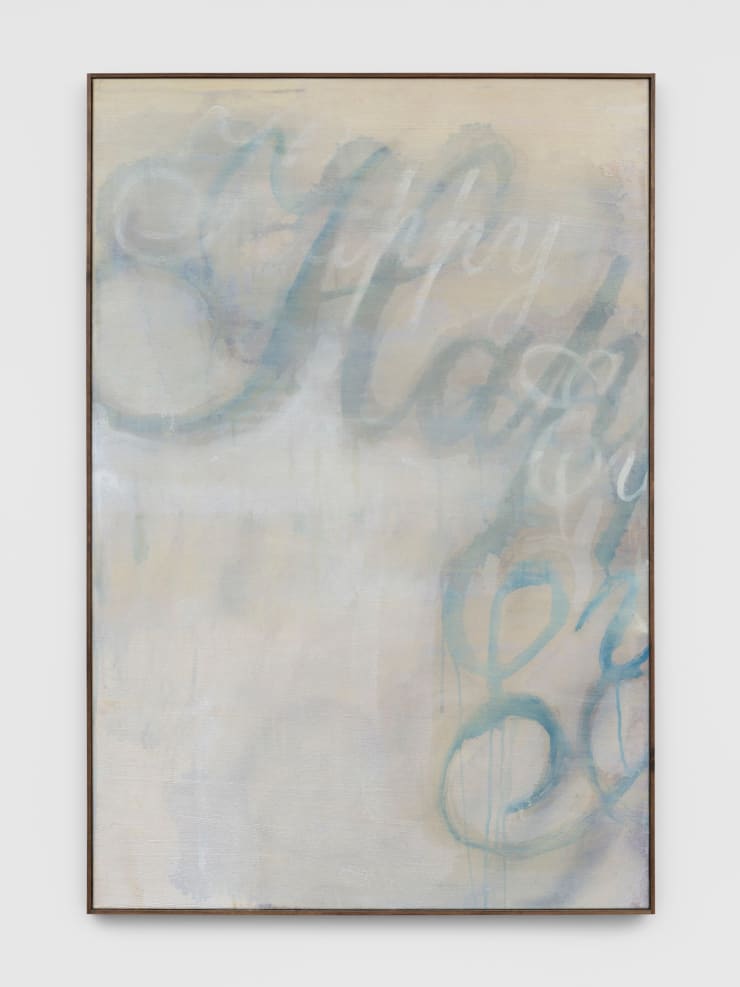

As for Gardner’s new paintings, I was not able to walk, sail, or fly to see them in person. I had to rely on superficial vision. But I think I can see something nonetheless about what they are, and how they are painted. As in “Distant Stars,” I detect a roughness of handling that puts an accent on the surface and makes the image almost intangible—not in the sense that the viewer is denied contact but rather that the contact consists of a kind of visual equivalent of feeling something slipping from your fingers. But the imagery is altogether different: the image of language. The very title of one of the paintings, If Only for a Moment, 2023-24, embodies this sense of the elusive—of desire unfulfilled and perhaps unfulfillable. And the painting and its title are in accord. The words, their cursive script floating there in no particular order as they emerge and dissolve, somehow communicates the essence of (as the Velvet Underground put it) “had but couldn’t keep.” Or look at Angel, 2024: The faint traces of the word among still fainter traces of arabesque marks that might or might not also be lettering seem to lay, not on the painting’s surface, but somewhere under a layer or layers of translucent integument. Could it be a faded tattoo? Faded, that is, like a memory one had wanted to inscribe permanently into one’s being, now receding? In any case, this painting conveys something hauntingly fleshlike. Forever, 2023, by contrast, seems to be more about an acoustic space than about a visible phenomenon—a recurrent echoing, yet that echo is always dying out rather than persisting. But Gardner translates this fading sound in tactile terms: as a kind of smudging of the repeating word. Will it repeat forever? That depends on who’s looking.

In resorting to language rather than pictures as the matter of his paintings, Gardner seems to be aligning himself with Yamamoto’s suspicion that vision is merely “superficial.” And yet as Gardner knows, words are, compared to images, more abstract. But they are never abstract enough to overcome the reality that meaning, as he says, “is ultimately fleeting - tied to too many circumstantial and personal factors to ever possibly be uniform.”

In order words, meaning, never quite absent, is always nonetheless in the process of escaping the painting that tries to contain it. Its traces are durable. Yes, you can touch them, smell them. But nothing is forever.

Barry Schwabsky is art critic for The Nation, international reviews editor for Artforum, and has recently contributed to publications on Pierre Bonnard, Issy Wood, Rose Wylie, and others. His recent books include two collections of poetry, Water from Another Source (Spuyten Duyvil, 2023) and Feelings of And (Black Square Editions, 2022).

-

Allan GardnerAngel, 2024Ink and Acrylic on canvas120 x 90 cm

Allan GardnerAngel, 2024Ink and Acrylic on canvas120 x 90 cm

47 1/4 x 35 3/8 in -

Allan GardnerForever, 2023Ink and acrylic on canvas40 x 30cm

Allan GardnerForever, 2023Ink and acrylic on canvas40 x 30cm -

Allan GardnerIf Only For A Moment, 2023-2024Oil on canvas200 x 175 cm

Allan GardnerIf Only For A Moment, 2023-2024Oil on canvas200 x 175 cm -

Allan GardnerAlways , 2023Ink and oil on canvas120 x 90 cm

Allan GardnerAlways , 2023Ink and oil on canvas120 x 90 cm

47 1/4 x 35 3/8 in -

Allan GardnerDreaming, 2023Ink and acrylic on canvas40 x 29.8 cm

Allan GardnerDreaming, 2023Ink and acrylic on canvas40 x 29.8 cm

15 3/4 x 11 3/4 in -

Allan GardnerEndless, 2024Ink and acrylic on canvas120 x 90 cm

Allan GardnerEndless, 2024Ink and acrylic on canvas120 x 90 cm

47 1/4 x 35 3/8 in -

Allan GardnerAlways and Forever, 2024Oil on canvas190 x 180 cm

Allan GardnerAlways and Forever, 2024Oil on canvas190 x 180 cm

74 3/4 x 70 7/8 in -

Allan GardnerEnending, 2024Ink and Oil on Canvas120 x 90 cm

Allan GardnerEnending, 2024Ink and Oil on Canvas120 x 90 cm

47 1/4 x 35 3/8 in -

Allan GardnerHappy A, 2024Ink and oil on canvas120 x 90 cm

Allan GardnerHappy A, 2024Ink and oil on canvas120 x 90 cm

47 1/4 x 35 3/8 in

(each panel)