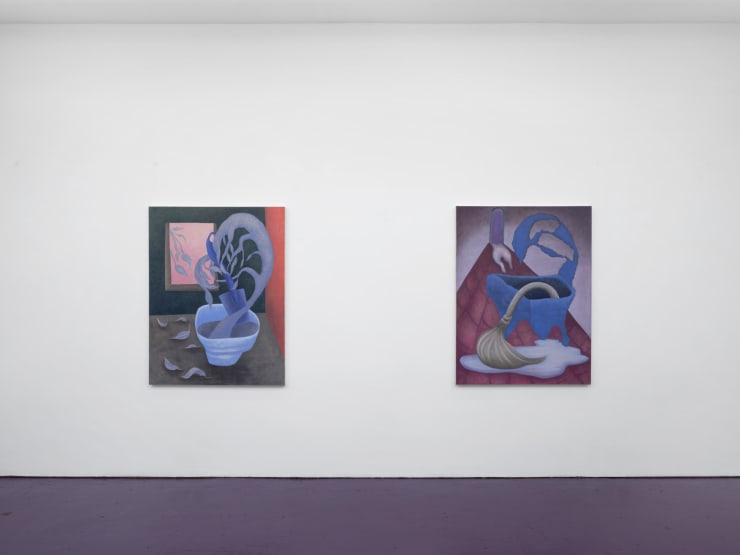

Busywork: Ginny Casey

Busywork and Bruised continue the gallery's dual exhibition programme, conceived to present the artists and their respective practices in tandem. Whilst exhibitions are to be experienced individually, they are curated to remain in dialogue with one another; the work suspended, in ‘conversation’.

Both Casey and Treiber’s work play with that which is recognisable and empty it of its familiarity, forcing the viewer to reconceptualise our relationship to these items and spaces. Taken together, their work reflects and refracts a similar preoccupation with specificity and absence and creates a shimmering dialogue categorised by surreal voids.

Perhaps just as much as the studio, the artist’s tools have been appraised for their service in the god-like gesture of creation by historians and storytellers alike. And the artist, in turn, beholder of that special something that ‘alchemically’ transforms mere substance into works of fine art, about which writers are so fond of writing. I’ll admit it has all the ingredients of an epic: we have the artist-hero cudgelled by divine inspiration, their giftedness in manipulating materials and so on. The mythicised artist turns prototypical Supreme Maker, fulcrum of a universe where nothing is or can be except through his mediation. When story hour nods off, the room clicks dark.

In the dark reaches of the night Busywork begins, détourning the oft-hawked cliché of artistic plight. It may be precisely this operation of upturning god-the-man’s house that entitles us to write one of those texts banding about Freud’s unheimlich, its relationship to ‘animism, magic and sorcery, the omnipotence of thoughts’. Further still, the inversion of guest-host relations, or the discovery of the stranger with whom you’ve been sharing a home. Behind the back of the waking, the domestic scene quietly rearranges itself: a lone mop takes up its position, prepared to command the stage…

Everywhere in Busywork we find sprung coils that make madhouse of the home: roiling and rollicking dining sets, self-deconstructing scissors adroitly rendered as visual puzzle. Sprung coils herald the revenge of the repressed: a cogent world left in bits and tatters: fragments of the anxiety dream that anguish its sleeper. In dusky, innominate settings, thingliness unleashes itself all over Busywork with cartoony belabour. The totalitarian of the Rule of the house is overrun by the democracy of things: the stable state of objecthood, stowed away in the cupboard and then just as easily dis-remembered, is bowled over by thingly agency. Frustrating the orderly and loosening fixity, coils everywhere here dramatise the thing’s concealed but autonomous machinations.

I realise there is no shortage of wordplay to be written about man’s ‘tool’ or the crisis of masculinity but, decentring him for one damn moment, Busywork is trained on feminine libidinal energy and the artist-mother’s personification as tool. If she attests to ‘make something I’m sympathetic to’, then the archetypal representation of the hammer, for example – with its farcically heavy head and bullish driving force, whose raison d’etre is the utilitarian achievement of aims – may not be quite right. Over the phone we paused to consider whether a mop even ‘counts as a tool’, which probably says as much about the tool’s status in our imaginaries as our failure to see acts of maintenance as labour in its own right. Nagging gripe notwithstanding, the fait accompli of patriarchy to invisibilise the feminine work invites practical consideration, because ‘it’s not magic, the housework doesn’t happen by itself’.

Repression and release, proxy and personification; the lesser tool hooves into view after the children are assured of a sleep unperturbed. Look better, dithering there, the faintest sense of her conveyed by brushed mark; the moulting mauves and post-partum blues; veils and shadows and feminine discretions; the insouciant scrawlings of her infant son grafted into the compositions, even. The glancing intimation of the painting titles, one of which I misread: a lapsus trading ‘domestic renovation’ for ‘domestic revolution’. But renovation does just as well, for who else makes and re-makes the habitable world once, twice, thrice over. Only hers, the anxiety of a continually flooding passage, the interminable work after-hours that by day is liable to come undone. Hers alone, a work deferring gratification then turned ethic, the sheer impossibility of its finality or completion is more than anyone can bear. Depletion replaces completion: not the satisfaction of the masculine tool, but the endurance of a feminised work that toils on, and on, and on.

Maybe these sour ruminations at some point turn melancholy, what seems to pervade Busywork despite all the humdrum, hustle and bustle. Or maybe, as we would otherwise have it, the incongruence of doing and un-doing heightens the stakes of a tragicomedy, in which alienation surely plays its part. The fullness of chore-doing melodrama sprung like a coil in Busywork’s undeniable humour, for her tools’ revolt is an anti-functionalist buffoonery: the window-gazing daydream sequestering productivity, the deflated mop handle that in its seeming surrender puts up resistance. Amid spangled multi-tasking limbs and inhuman tensile strength, this soft subject stars in her own production of work.

Press