A Timeless Story: Chechu Álava

“Beware a woman who dreams” – Clarice Lispector, The Burned Sinner and the Harmonious Angels.

“Who shall measure the heat and violence of the poet’s heart when caught and tangled in a woman’s body” – Virginia Woolf

“I paint these portraits knowing that these women are not perfect. They are vulnerable, they do not pretend to be examples and I admire them even more for that, because I too know what it is to struggle, to learn, to evolve, to be imperfect.” – Chechu Álava

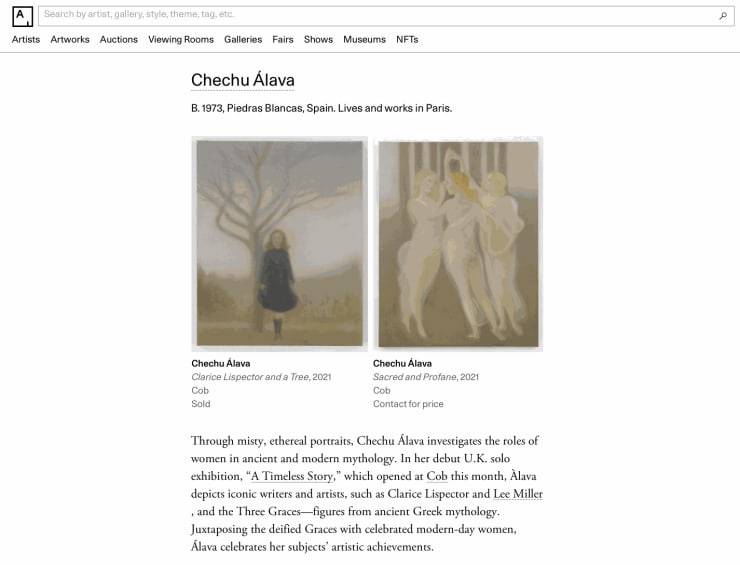

Cob is proud to present A Timeless Story, the debut UK solo exhibition for Spanish artist Chechu Álava.

For the last decade, Álava has produced an ongoing series of painting portraits that seek to unify and align the depictions of ancient and mythological female protagonists with that of modern and contemporary feminist icons, female intellectuals, writers and artists. A Timeless Story follows on from two presentations of the same painting series in the last two years – The Restless Muses at BravinLee programs in New York (2021), and Rebeldes, Álava's solo exhibition at the Thyssen-Bornemisza National Museum in Madrid (2020).

A Timeless Story brings to Álava’s canon a focus on the representation of female literary and poetic icons to examine the position of women in a male-dominated literary sphere. Like the other women to feature in her portrait series, these extraordinary historic figures are arguably bound together by their rebellious pursuit for individual artistic expression, bringing the feminine experience to the fore. A Timeless Story not only refers directly to these literary heroines, but also signifies Álava’s retelling of a broader story of female representation across time. In conjunction to this, the exhibition title A Timeless Story pays tribute to the traditions found within the history of painting, which Álava refers to as her “inexhaustible, endless and timeless source material”.

From a personal standpoint, Álava chooses to portray these female artists, poets, and creators both as way to honour them and to investigate the facets of her own identity and lineage through their likeness. These portrayals are interconnected – each one a sum of a larger part, an individual thread woven into a larger tapestry. As we move from one to the other, and by way of the paintings’ unifying features such as palette and mood, our awareness shifts from that of the subjects’ literal portrayal, to understanding them in direct relation to one another. In this moment, we perceive them as one and the same. This concept is further compounded by the alluring, hazy surface texture that envelops the portraits and has come to typify Álava’s practice, a tool that harnesses ‘essence rather than appearance’. Álava explains that she is not so much looking for “the material or physical aspect of the subject, but for the soul of things”. Overall, we are reminded of the ornamental Russian Matryoska doll and the traditional representation of the mother carrying a child within her – a chain of mothers carrying on a legacy through the child in her womb. Symbolic of the continuation of life and the unity of body, soul, mind, heart, and spirit – so too can Álava’s paintings be viewed as one born from the next.

Separately, Álava asks those who encounter the works to consider resituating these women outside of a patriarchal lens and the constructs that pervade the history of art where depictions of women have, more often than not, only reflected male desire. Much like her previous works from the series, the portraits in A Timeless Story invite us to reflect overall on the genre of portraiture through the complex, often extraordinary lives and personalities of these women who were often judged by the male world in which they fought to find a place.

A portrait of Ukranian/Brazilian author Clarice Lispector is included in the series – considered one most important Jewish writers of all time (although she cannot escape the comparison to her to male author counterparts such as Kafka and Joyce, Beckett). Much of her literary characterisations often reflected her personal story at the time of writing – a record of a woman’s entire life, written over the course of a woman’s entire life. As such, it seems to be the first such total record written in fiction, in any language. Her characters struggled against the ideological notions about a woman’s proper role. Her sympathy for silent or silenced women haunts her stories – her works have been likened to witchcraft. Similarly, there is a double portrait of the Russian poet Anna Akhmatova and her cabaret actress friend and lover Olga Glébova-Soudeïkina taken from a rare photograph of the pair. Akhmatova is one of the most significant Russian poets of the 20th century. Constantly under the threat of artistic repression, her work was condemned and censored by Stalinist authorities and for many years was disseminated through word of mouth. She is notable for choosing to remain in the Soviet Union, acting as witness to the events around her. It is arguable that the recurring focus on the devastation of Mary, mother of Jesus, in her poetry, is symbolic of the ravaging of Russia, particularly in relation to the harrowing of women in the 1930s.

Another double portrait of the artist Suzanne Valadon features alongside her son, the artist Maurice Utrillo. Valadon was known for her bohemian life and rebellious attitude and, at one point, became the first woman painter admitted to the Société Nationale des Beaux-Arts. As an artist, the subjects of her drawings and paintings included mostly female nudes, portraits of women, still lifes, and landscapes. She was a model for renowned artists Pierre-Auguste Renoir and Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec.

In tandem to its literary theme, A Timeless Story throws a spotlight on the complex yet enduring stereotype of the female muse-male artist relationship. An interplay that is most literally signified by her re-interpretation of Botticelli’s Three Graces into Sacred and Profane,as well asEdvard Munch’s Puberty Madonna into Confinement After Munch. Álava exploits the immediate recognisability of the ‘great masters’, using these as entry points to explore, more broadly, our acceptance and understanding of the female image through the eyes of men. Rather than rescue these women, and by implication suggest their victimhood, Álava breathes new life into the images, in a subtly provocative way. This is an irreverence that is heightened in her short film Plein Air, in which the question of women as credible artistic figures is turned playfully on its head in its recalling of a silent movie aesthetic, relieving us, for a moment from the hyper-critical artist’s gaze.

With this in mind, these images activate the portraits of Lee Miller, Suzanne Valadon and Anna Akhmatova and Olga Glébova-Soudeïkina – all of which have been specifically cited as muses in their lifetime yet had their own successful careers. Some would argue these women were judged for their appearances in the work of a male artist, rather than assessed on their own merit through their work. Olga Glébova-Soudeïkina was a symbolic figure of the Silver Age. She was an actress, dancer, painter, sculptor, translator and one of the first Russian fashion models. People called her ‘Beauty of the Silver Age’, ‘Columbine’ and sometimes ‘Decadence Fairy’. Akhmatova became renowned, not so much for her beauty, but for her ‘intense magnetism and allure’, attracting the fascinated attention of many great men, including Modigliani in Paris, who created at least 20 paintings of her, including several nudes. Lichester, a former fashion journalist, has been referred to ‘looking like Marlene Dietrich and writing like Virgina Woolf’. Álava’s subtle inclusion of a portrait titled Simone Rocha Girl brings a contemporary stance to this continuing obsession with the voyeur and the voyeured.

Another subtle subversion of the artist-muse relationship comes in the form of a miniature work depicting a couch and titled The Lounge. Devoid of figures, Álava transforms this seemingly innocent domestic still life into a loaded symbol of the arena from which ‘female emotional hysteria’ was diagnosed, scrutinised, and tamed by the intervention of the male psychoanalyst. Elsewhere, portraits of anonymous women are titled after their emotions – perhaps in reference to the misogynistic perceptions of the irrational female. Through these works, Álava invites us to chart the journey of the female artist/muse through the refracted lens of her canvas. In retelling these stories, she reclaims the muse identity from the patriarchal lens, thus her figures push and pull between strength and vulnerability, beauty and agency. Their stories and selves collapse to create new, quieter moments of reflection, in which we question: is beauty a timeless quality, or a misogynistic construct?

Or perhaps we can simply understand this work as a springboard from which to unpack the myriad complex lives portraits, identities, and vulnerabilities of the women that Álava chooses to include.

Moody and existential, these portraits are imbued with a muted tenor of unspoken intensity common to many humans who currently identify as women, whilst celebrating the shared and common positionality of womanhood across the veil of time. These remarkable figures are both rebels and heroines for the younger generations that are learning from their experiences and resilience.

Featured Press

-

Chechu ÁlavaSacred and Profane, 2021Oil on linen116 x 89 cm

Chechu ÁlavaSacred and Profane, 2021Oil on linen116 x 89 cm -

Chechu ÁlavaArtist and Model (Lee Miller), 2021Oil on linen55 x 46 cm

Chechu ÁlavaArtist and Model (Lee Miller), 2021Oil on linen55 x 46 cm -

Chechu ÁlavaClarice Lispector and a Tree, 2021Oil on linen41 x 33 cm

Chechu ÁlavaClarice Lispector and a Tree, 2021Oil on linen41 x 33 cm -

Chechu ÁlavaThe Writer's Table (Virginia Woolf), 2021Oil on linen55 x 46 cm

Chechu ÁlavaThe Writer's Table (Virginia Woolf), 2021Oil on linen55 x 46 cm -

Chechu ÁlavaTaming Emotions, 2021Oil on linen130 x 162 cm

Chechu ÁlavaTaming Emotions, 2021Oil on linen130 x 162 cm -

Chechu ÁlavaConfinement (After Munch), 2020Oil on canvas116 x 89 cm

Chechu ÁlavaConfinement (After Munch), 2020Oil on canvas116 x 89 cm -

Chechu ÁlavaThe Lounge, 2021Oil on linen27 x 35cm

Chechu ÁlavaThe Lounge, 2021Oil on linen27 x 35cm