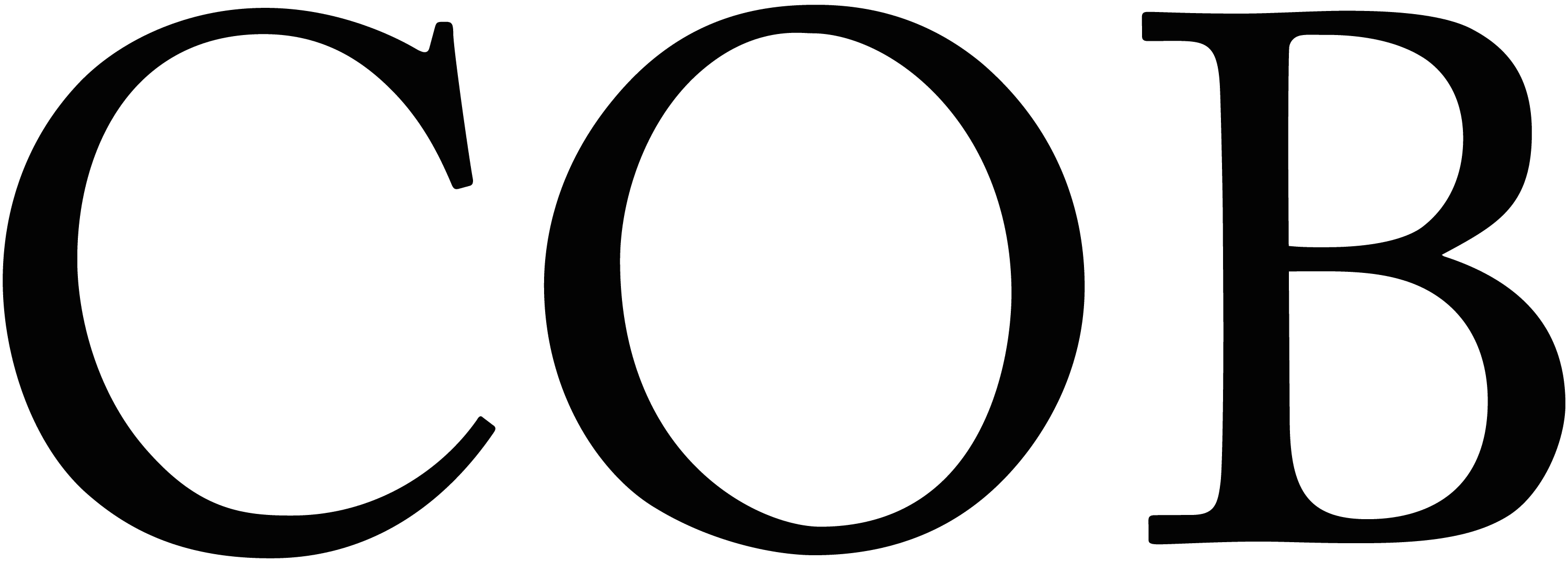

Rural Scenes: Cat Roissetter

Cob Gallery is proud to present ‘Rural Scenes’, a new exhibition of painted works by Cat Roissetter.

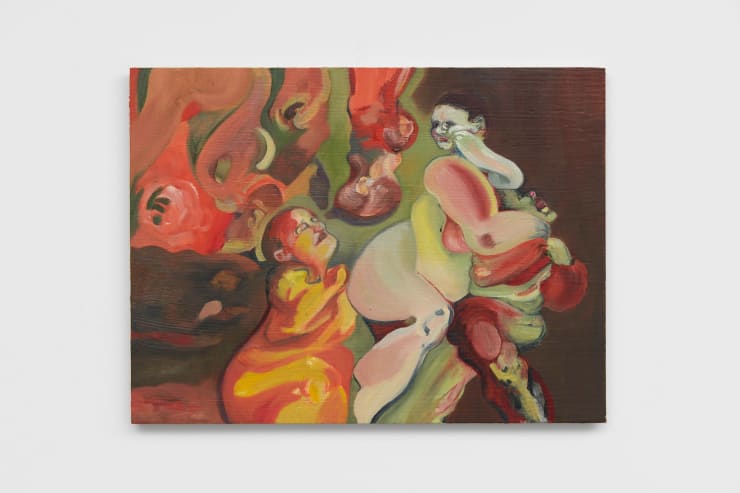

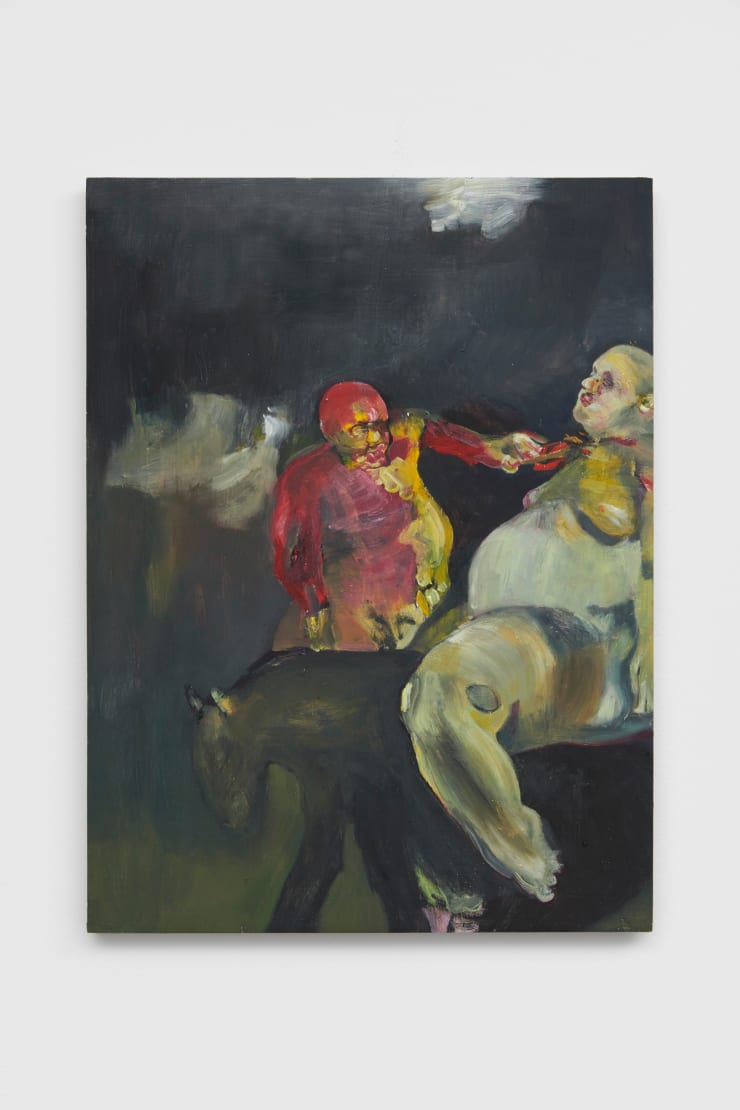

Opening a new window onto the artist’s subversive dream-world – an unsettling, equivocal space that emerges from a distinctively English cultural imaginary – ‘Rural Scenes’ finds Roissetter turning away from the pencil and crayon of her earlier work. Instead, she uses oil paint on gesso-primed timber surfaces. The layered translucency of the drawings cedes place to a markedly thicker, darker tonal register, yet in other ways the transition is a natural one: Roissetter’s earlier use of graphite and wax in combination with linseed oil already had a liquid, painterly quality about it, and the shift to oil paint allows this to emerge with a new and different force.

The change of medium is bound up with thematic transitions. Where the bloated, lethargic cherubs of Roissetter’s work previously occupied a diaphanous, ethereal space, here they seem to fester in troglodytic penumbras: ambiguous rural settings that draw on the artist’s interest in painting directly from natural scenes. Airy sylphs have become sullen gnomes, clustered in the shady nooks at the back of the garden. Brooding busily like the cast of some medieval Netherlandish nightmare, ritualistically coupling or conferring over an obscure task, they appear at once ceremonial and disorganised: possessed by the uncertain resolve of dream. Their fleshiness and earthiness are counterweighted by a tonal abruptness that gives the effect of superimposition or projection: conspirators caught unawares and captured at the scene of an unspecified crime.

Where Roissetter’s previous work has involved subjecting her materials to various processes of physical degradation and weathering, ‘Rural Scenes’ sees this built into the provenance of her source material: degraded and fuzzy surveillance footage and cheap touristic snaps, depicting scenes of congress and conflict that Roissetter reimagines into diffuse narratives. Luxuriating in their listless sexuality, her figures themselves also appear to be ‘degraded’ to a medieval stew of bodily needs and desires. Like grace-and-favour hermits populating some debauched landscape garden, they linger in the shadows of the artifice that surrounds them. In mute frenzy they mete out their obscure punishments and attend to their untrammelled lusts, supplying a dark and disconcerting parallel to our own supposedly enlightened world.

-

Cat RoissetterLilac Wine, 2022Oil on panel40 x 30 cm

Cat RoissetterLilac Wine, 2022Oil on panel40 x 30 cm -

Cat RoissetterSkin the Fool I, 2022Oil on panel30 x 40 cm

Cat RoissetterSkin the Fool I, 2022Oil on panel30 x 40 cm -

Cat RoissetterLoomer, 2022Oil on panel30 x 40 cm

Cat RoissetterLoomer, 2022Oil on panel30 x 40 cm -

Cat RoissetterRunning in the Red Night, 2022Oil on panel30 x 40 cm

Cat RoissetterRunning in the Red Night, 2022Oil on panel30 x 40 cm -

Cat RoissetterSquelch Thee, 2022Oil on panel30 x 40 cm

Cat RoissetterSquelch Thee, 2022Oil on panel30 x 40 cm -

Cat RoissetterHistamine, 2022Oil on panel30 x 40 cm

Cat RoissetterHistamine, 2022Oil on panel30 x 40 cm -

Cat RoissetterHig Reap, 2022Oil on panel30 x 40 cm

Cat RoissetterHig Reap, 2022Oil on panel30 x 40 cm -

Cat RoissetterBereft, 2022Oil on panel40 x 30 cm

Cat RoissetterBereft, 2022Oil on panel40 x 30 cm -

Cat RoissetterSkin the Fool II, 2022Oil on panel40 x 30 cm

Cat RoissetterSkin the Fool II, 2022Oil on panel40 x 30 cm -

Cat RoissetterA Butcher's Life, 2022Oil on panel40 x 30 cm

Cat RoissetterA Butcher's Life, 2022Oil on panel40 x 30 cm